In the Shadow of Young Scammers in Flower: Caroline Calloway Arrives

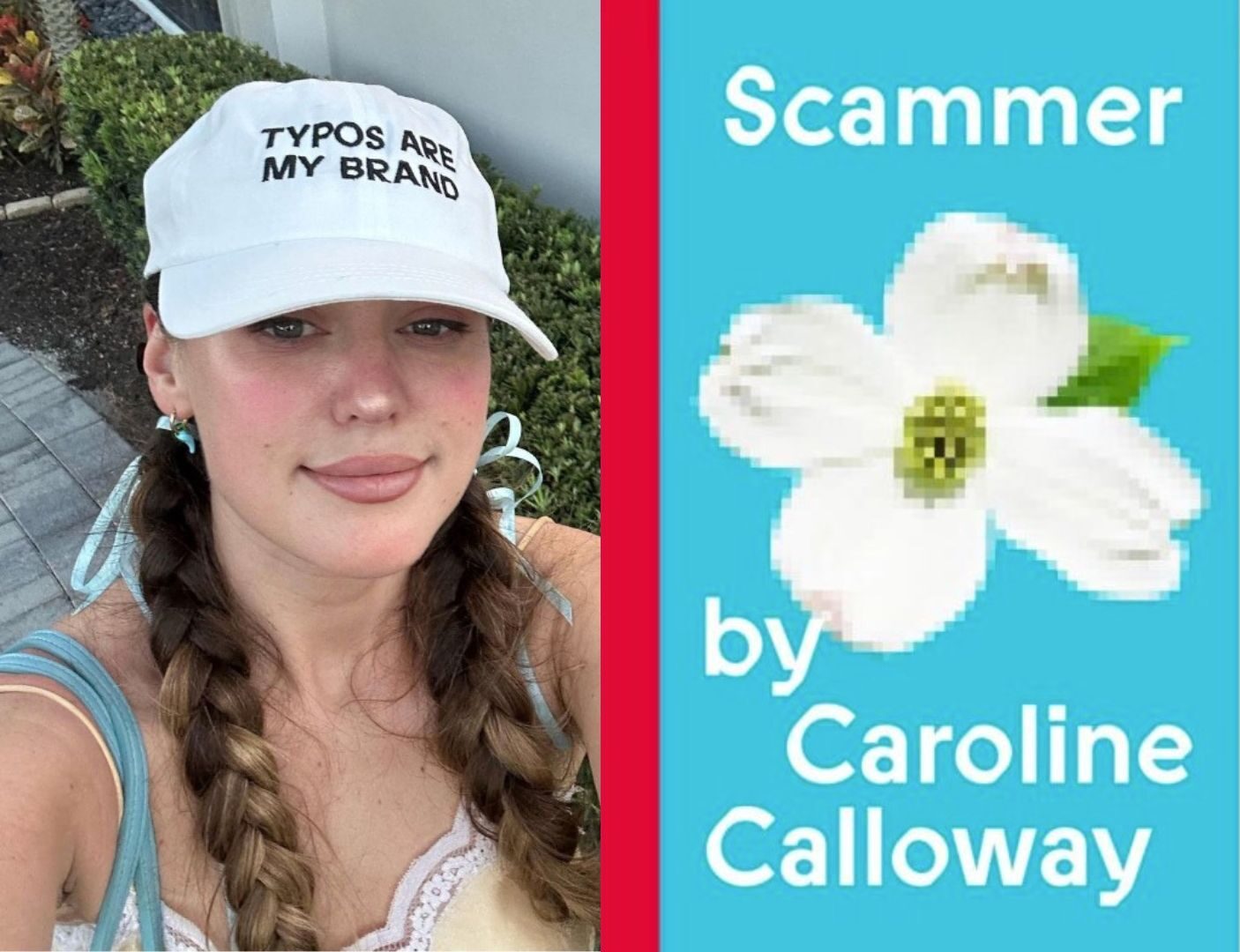

Caroline Calloway/Instagram

I have only just read a small and lushly-produced daybook (intended to be read during the course of a day) self-published by Caroline Calloway that is not quite or really about scamming at all. Entirely coincidentally, I began reading Scammer (2023) while on a daybed (an assumed, nearly said, expectation and outgrowth of the intent derived from the term “daybook” – which is coined in the daybook) and through one intervening restaurant and hotel lobby read most of this memoir on our seafoam chaise, which was purchased second-hand earlier this year from an actress leaving Los Feliz, because it fit the color scheme, was said to be (and is) “soft,” and because the indentations and marks in the Cannes velvet were imperceptible through the Facebook Marketplace pictures.

If you don’t know much about Calloway, and I am unable to embark on a serious study here, this should suffice: she is a living writer, who, like formerly-living Peter Matthiessen has found something inspiring and solace-giving about Florida, and who writes about life observantly, sincerely, and from various vantage points while taking “butterfly-wing-powder artistic risks.”

Often, the kind of popular writing published in English comes by way of writers who: (1) lack interesting (non-dogmatic; not banal) ideas about art and culture; and/or (2) are not particularly perceptive; and/or (3) may be capable of rising above one or both of the preceding but who can only (are only allowed to?) give us their work in prose that is serviceable at best. It’s refreshing to come across a writer with: (1) compelling ideas (in Scammer they are novel, timeless, and probably something else); (2) fluid observational adroitness; and (3) really good words.

The reader is immediately struck by the intimacy and immediacy (but how when looking backwards? this is a great question; a greater feat) of Calloway’s prose – an overflowing urge to account for so much – not entirely unlike a trait we recognize in admission-granting self forgiveness. This is the basic emancipatory thing.

The syntax in Scammer is sometimes idiosyncratic. But Calloway’s sentences are not showy, flowery, or even half a shade of purple – they are leapingly bold. And they are not likely to please the graph paper-nibbling, undead grammarians and tin-eared, finger-wagging prescriptivists, always staring backwards, who cart around rules of form and rubrics for style as if those are anything more than the decades-piled-up, the combined hubris of the mid.

The sentences often snake and drag you along – sometimes from one page to another. Meanwhile, there is a speed and urgency in the words that frequently drops the reader into clutches of moss and clover. A quickness from incidents of baring herself, raw-on-the-bone, to self-deprecating passages, and, then, settling into tender sheets of warmth and vellum. This often feels poignant. A face that feels so flushed something must be bleeding. And, as another writer once noted, style is not ancillary: “it cannot be separated from the thought or the impression.”

An energetic pace frequently turns to something short of frenzy. A fourth wall is broken as a journalist cuts in to tsk-tsk. The style veers from conversational to lucid and deft prose that would be well-at-home describing a Vermeer – maybe spotting a cut flower in the hand of a person standing at the shore in a painting of Delft where no tulip actually exists. But wait: that’s one of the flowers Calloway has given us with Scammer – which all decent book shops should be selling eventually.

It is exciting to have writing like this and know that it portends more writing like this. Calloway writes with a glad, ecstatic delight and she is a delight to read.

***

We could make the mistake of believing we know about a writer from press clippings at legacy publishing houses. We shouldn’t do that here.

There’s a good amount of well-earned scorn from the memoirist not particularly happy that other writers – paragraph-pushers of lesser styles: writing to the neutered-and-spayed technical jargon of in-house or imported style guides; writing through parasocial paralysis in dire need of virality; writing in the increasingly cloying lesser sturm of instantly-dated and unfortunately-still-resuscitated early aughts blog snark – have taken it upon themselves (while on the hunt for paychecks, residuals, salary bumps, notifications) to tell pieces of her story. Well.

Other, absolutely fine, reviews of Scammer have retold key moments (and will have done so with more judicious instincts), so, in lieu of the publicly-available and the author’s wishes: please just read the book. The first edition is only being sold, as far as I can tell, online through Calloway’s website here. The volume is beautiful – resplendent in presentation and keenly focused on the tiniest details. The luxury hardcover’s soft matte finish is set with 19ème siècle-style marbled endsheets and a typeface with a (redemptive-in-miniature) story of its own.

Maybe some of the prose seems too good in service of, at times, tearing down the version of Caroline Calloway from That One Essay – a version that always seemed to live in an obviously caricatured reality it could only appeal to a certain kind of credulous content consumer; the audience for Millennials vs. Mechaboomer stories; the ones who think a Pew-defined generational cohort are killing the industries and fashions necessary to their idealized visions of American culture and consumption; those with idealized visions of America; West Wing fans. Maybe not.

When a “murmuration of darklings, feathered and murderous,” appear with black ink to stake a claim on your life like an absentee landlord in Yafa, maybe it’s incumbent on hewing to a campaign of refutation – both for the writer, herself, and for the boring things those claims represent.

(And for those interested in all of that. There are some acid lines about the drama. There is a thematic series of rendezvous with a double-punch payoff. And, since I’ve got you here in this parenthetical: there is an answer to the question about how long an adult should perform penitence for Instagram captions. Moving on.)

***

In some sections about invalidity, in the British sense, Calloway, with a novelist’s eye, hits upon a Proustian truth about the nature of illness, immobility and the effect those conditions can have on people who spend their time staring “at the tips of trees” while planning “a next life” as a “decoder, celebrant and memorialist” amidst a “veil of daydreams between [themselves] and reality.”

There are, in Scammer‘s fewer than 200 pages, no shortage of touching-tender-funny scenes. And the brevity of the daybook makes the reader feel like they are clued into a secret literary chapter; almost a vanishing act of explosivity. There is, as mentioned, not much in the way of scamming; at least not by the author; at least not the kind with victims; at least not hers. But there is a politically-motivated theft from a tony club that provides a moving-not-mawkish end of something.

Interrogations of social class in Scammer take on some truly trenchant dimensions when Calloway translates snippets of her Anglophile-scattered past – part beloved, part debauched – and offers glimpses (for now) of fingerprints left to melt the Cadbury bars of dead Empires, bored pretenders, and still-proud well-breeders at Cambridge and U.S. Supertrustfund sites teeming with obscene, inherited wealth.

Florida looms large – an unlikely savior. As does New York City. There’s the yuck of Los Angeles and its slow-dissolving dreams like kisses. In terse images there is important work being done about the geographic finality of each American place. Because this isn’t a nation but an agglomeration of opposites dotted with billboards and street-visible logos connecting us across mile markers. In this reverse amalgamation we are constantly pulled apart and reconstituted into an unworkable polity that would have made Rousseau hit the nipple and quit before he started.

With places as layovers, Scammer excels by way of its domestic and transatlantic journeys through, and then the reader’s proximity to, sorrow. Calloway does that rare thing where all this sadness and mess is made fecund and transliterated into something that allows us to consider “life as a whole and in reality.”

Skilled is the memoirist, who, in reciting – in whatever form fits the narrative; and in Scammer the styles vary considerably between (sometimes within) each chapter; wink-nodding at one author in particular with an almost explicit callback to how his own sort of talent was described while eschewing, and running repeatedly over, the advice he famously gave Sheilah Graham about exclamation points – her own life forces us to, without prodding, recall better parts of our own.

We don’t feel drab or beat-down sad or superficially pained stumbling through the muck Calloway recounts in her memoir – though it is rife with remarkably bad feelings; decidedly awful experiences; the unknowable death of a parent – but, instead the reader is bobby-pinned to the wings of a fluttering thing as it is shakes off the cocoon or chrysalis. There’s a process here: an opportunity we’re invited to take part in. So, even when the memories hurt we can sense a certain strength and enlivening spirit that exists outside of time even in the lowest passages.

“I write for the girls who want fun above all else precisely because once they finally get it these girls can barely feel it,” Calloway writes. “I write for the girl I once was.”

To quote another writer for maybe the third time, there is a “species of eternity” in this kind of writing; something that, I think, will last longer than the kind of melancholy, somewhat angst-ridden, and sentimental essays of the moment.

There is a lot of ink in this budding daybook extolling the necessity of a writer writing the book they want to (need to?) write. Calloway does not explicitly state out-right whether Scammer is that book – but it’s clear that it is integral to a coming body of work that will include such books; to the creation of the real version of Caroline Calloway, the writer. This is how we really should meet her.

***

There is so much taken for granted in the text of what we are used to.

For a long time in life, people can be more interested in reifying the platitudes they pick up through repetition. They grow comfortable giving safe harbor to cliché as tropes are easily repackaged and cast as our own loving lodestars – a soak in the familiar. I don’t think Scammer does, plays to, or reinforces any of that.

It is rare and somewhat unsettling when we read a book so profligate with ideas. Remember: this is not a country that is used to ideas. Even our reading public (a good idea!) is not quite used to ideas. The reasons for this are varied, big, and mucho. In the era of takes on the Scoville scale even some of us who know better have soured on ideas that didn’t exist when we were in college. Or we see the diffusion of then-interesting ideas and shirk away, shrinking back from thinking hard again, because we never thought the new would leave the confines of the ivies, public and private, should not be anything more than larks for brains surrounded by columns and master-planned communities styled on the Spanish Renaissance.

We are not used to public figures with interesting thoughts unless they can be kick-boxed into corners, pummeled, and flagellated to the tune of “stop hitting yourself.” It is said that “on TV they prosecute anyone who’s exciting” and on the internet they hand out filleting knives and last known addresses in exchange for a working email address and quick-clicked data to feed the self-driving cars.

This book is a reminder that it’s okay to dream big, Millennials, a solid and well-placed nudge that says you can live beyond and eclipse the internet-fueled, atomized American urge to “screw each other over for a jolt of satisfaction.”

There is a de rigueur depression as some of us sift away the echoes of the past and lapse away from the long, hose water summers of the 1990s – a decade romanced almost single-handedly by Stephan Jenkins’ lyrics – but Calloway reminds us that then “we were all radicalized bigots” who, as children, tossed around epithets until some kind and strong enough adult told us what the words really meant.

In its forthrightness and through the reality of its publication, the aspirational heft of Scammer is an electrifying realization itself – against generational discourse and the meme-like collective despair that occasionally takes root via weaponized nostalgia that feints at “better times.” Scammer is the useful memoir that is like “a drawbridge thrown across from the present to an already distant past” and helps us battle against some of the still-creeping anti-modernity and reaction.

•••

Reading Scammer is what it is to be gobsmacked.

Calloway’s prose is triumphant without being triumphal. The pacing in Scammer is elaborate and hop-scotch; back-and-forth; and all at a time. Frenetically enrapturing prose wraps up the ideas like someone in a far-flung pub on vacation pouring and you can, but you won’t, you don’t want to, say: “When.”

The daybook asks a number of questions, supplies some answers, and leaves a few ringing as devices – with promises of a future bouquet. Calloway sketches out a vision of her own aesthetics, incomplete, but we’ll wait as the cross-hatches fill in with yet-to-come entries. Frequently another (next?) book is teased throughout Scammer – actually at least two-and-a-half forthcoming books are mentioned.

Other questions; not stated in Scammer – bubble up: What if a worthwhile, maybe even important, voice was being churned into something else by the reflexive whims-and-clicks of the hate machine? Was being largely ignored for what they knew and could show they did best and better than certain scribes and detractors? Was being ridiculed by the “highly select mob” of discerning misogynists? Proust, the unreadable, day-avoiding, society gossip, had to self-publish at first, too.

Calloway approaches love from multiple angles – extant and former friends, once and could-be lovers, parents here and gone. Near the end of Scammer, the narrator notes her age and how “there are chambers of my heart that I’ve still never been inside.” Once she does get into those, understands them, and finds a way to tease them out into more screaming-and-winged blocks of text – whether that’s in another daybook or in longer form – we’ll all be all the better for it.

Calloway writes with an attentiveness – to the reader; to lurking truths – that presents itself as (and is) an immense, excited joy. Scammer is not some love song whispered in our ears, but a heartfelt focus on, genuine, crazy, “books and love.”

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓