NYT Opinion Piece Argues Trump ‘Might Have A Case’ On Birthright Citizenship

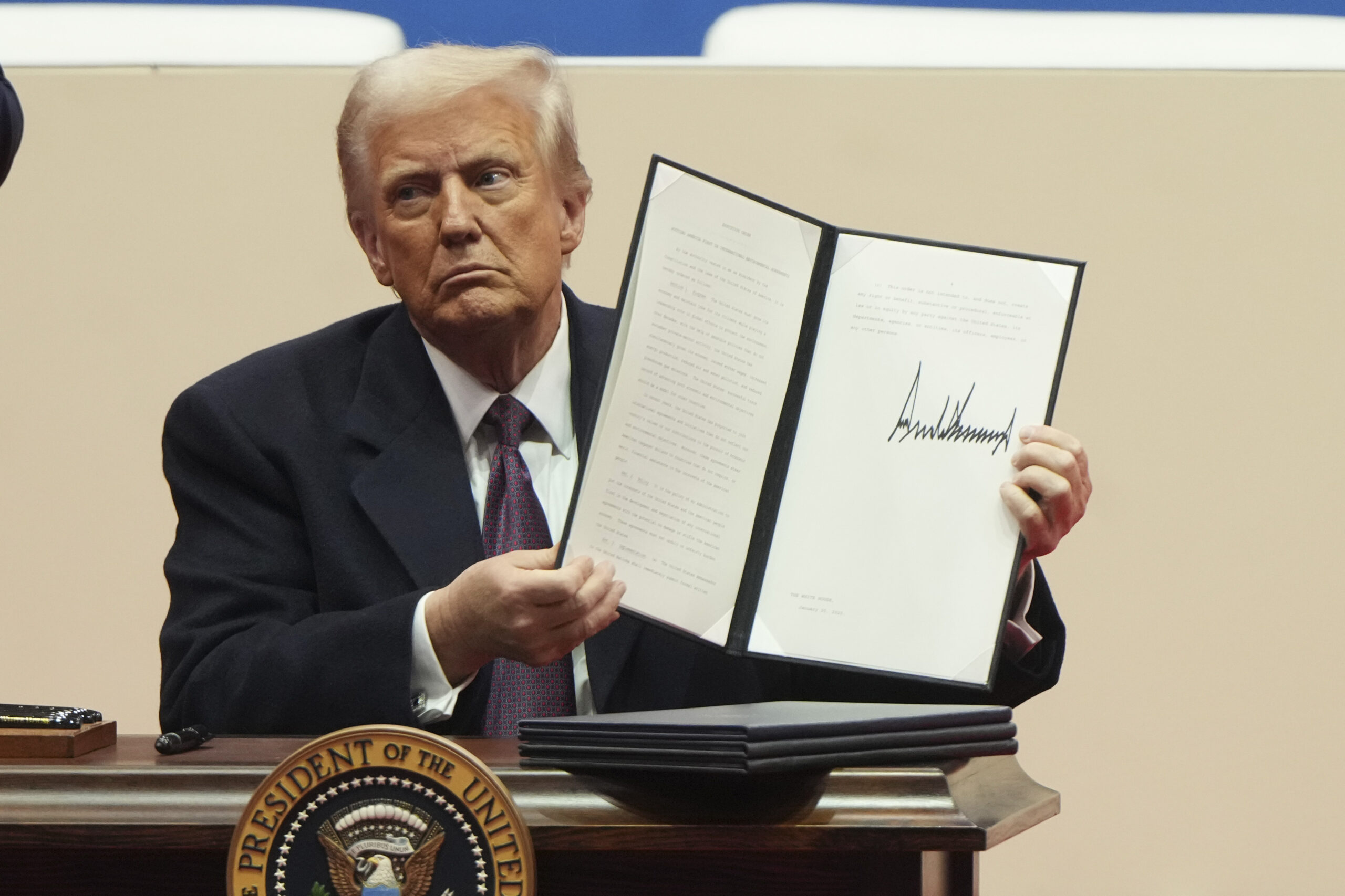

AP Photo/Matt Rourke

Two constitutional scholars argued in an opinion piece published by The New York Times on Saturday that President Donald Trump might “have a case” regarding his embattled executive order attempting to end birthright citizenship for the children of illegal migrants.

Professors Randy Barnett and Ilan Wurman wrote that although it has been argued Trump’s order is at odds with language in the 14th Amendment, there could be more nuance to the issue.

Barnett and Wurman made a case for why Trump could ultimately succeed in challenging the most common interpretation of the 14th Amendment’s “subject to the jurisdiction” clause.

They argued that the key question could come down to not where a person is born but whether that individual’s parents had ever entered into a social compact with the country – something they said had not been strictly addressed in numerous landmark cases dating back to 1830:

The answer most legal observers give is that it includes virtually anyone born on American soil, including those whom the order is meant to exclude, namely children born to parents in the country illegally or temporarily. Indeed, on Monday, the American Bar Association described the order as an attack on a “constitutionally protected” right. Federal judges in four states have enjoined the order, with one claiming that it “conflicts with the plain language of the 14th Amendment.”

Not necessarily.

The Supreme Court has held, in the 1898 case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, that children born here to permanent residents are citizens. But it has never squarely held that children born to those illegally present are citizens. When the court addresses that question — which it almost certainly must — it should consider the 14th Amendment’s original purpose and the common-law principle of “jus soli,” or birthright citizenship, which informed the original public meaning of the text. Both relate to the idea of social compact and contradict today’s general assumption that the common-law principle depends solely upon place of birth.

Per Barnett and Wurman, common-law principle traditionally excluded children of foreign diplomats, Native Americans, and others outside the “jurisdiction” of the US.

Native American citizenship was decided by the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

Barnett and Wurman also addressed those whose parents were “present in the United States illegally,” which, again, they said had not been strictly addressed regarding the children of illegal migrants in other cases argued before the court.

The two asked, “Has a citizen of another country who violated the laws of this country to gain entry and unlawfully remain here pledged obedience to the laws in exchange for the protection and benefit of those laws?” They continued:

Clearly, the parents are not enemies in the sense of an invading army, but they did not come in amity. They gave no obedience or allegiance to the country when they entered — one cannot give allegiance and promise to be bound by the laws through an act of defiance of those laws. Such persons can even be summarily removed from the country without judicial procedures of the sort that would protect citizens. If the allegiance-for-protection view informed the original meaning of the text, then they and their children are therefore not under the protection or “subject to the jurisdiction” of the nation in the relevant sense.

Barnett and Wurman concluded that should the Supreme Court revisit the issue of birthright citizenship, justices might rule Trump has a valid argument.

“When they finally consider this question, the justices will find that the case for Mr. Trump’s order is stronger than his critics realize,” the pair wrote.

Trump issued an executive order on the matter on Jan. 20 which he said would protect the “meaning and value of American citizenship.” The order has been blocked by numerous federal judges.

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓