Right, Left, and Media Reject What Salman Rushdie Calls ‘Absurd Censorship’ of Roald Dahl’s Children’s Books

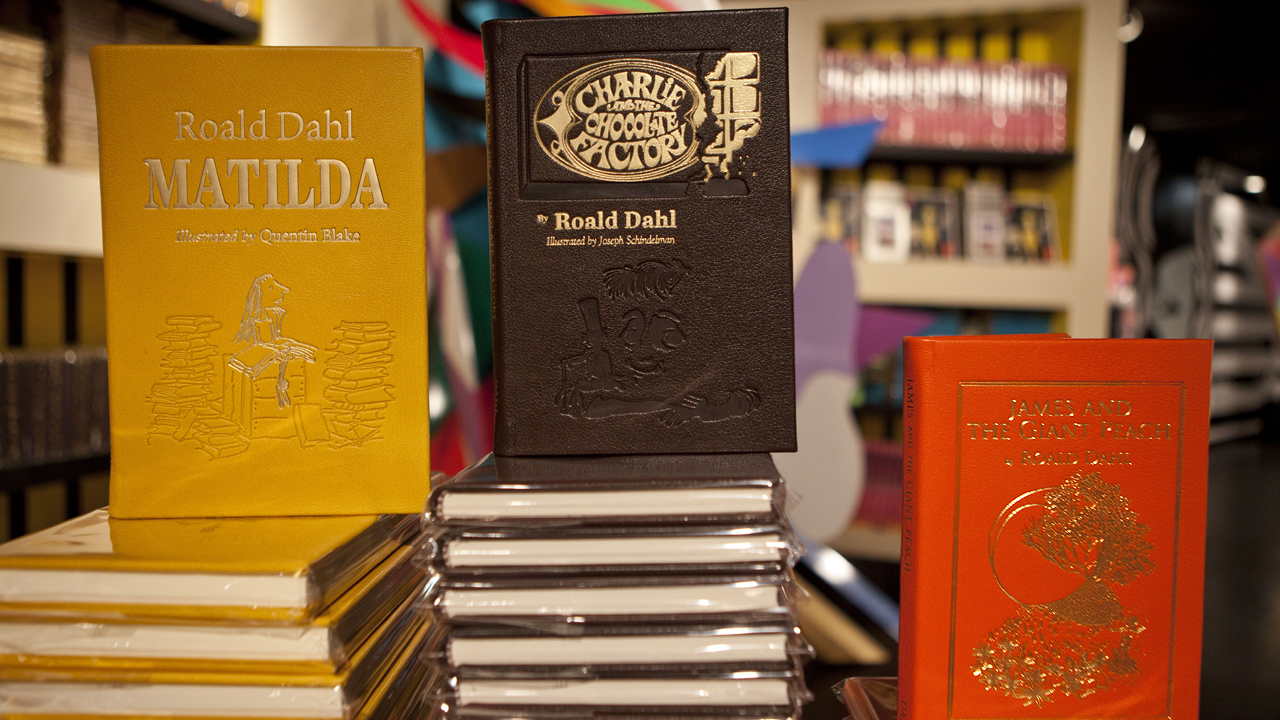

AP Photo/Andrew Burton

Classic books by children’s author Roald Dahl are being edited and altered, with some lines changed, others removed, and some new content not written by Dahl inserted under the pretext of “sensitivity” and modern sensibilities, it was reported this weekend, prompting widespread, bipartisan rejection from almost all quarters.

From Dana Perino to Salman Rushdie, from National Review to the Washington Post, from Twitter to CNN, Americans broadly objected. Rushdie’s tweet made a particular impact.

The Telegraph had the definitive first article on the posthumous rewriting of Dahl, and included multiple animations to illustrate some of the changes. Here are a few of those, but the full impact can only be seen in The Telegraph’s full article.

From that article:

“Words matter,” begins the discreet notice, which sits at the bottom of the copyright page of Puffin’s latest editions of Roald Dahl’s books. “The wonderful words of Roald Dahl can transport you to different worlds and introduce you to the most marvellous characters. This book was written many years ago, and so we regularly review the language to ensure that it can continue to be enjoyed by all today.”

Put simply: these may not be the words Dahl wrote. The publishers have given themselves licence to edit the writer as they see fit, chopping, altering and adding where necessary to bring his books in line with contemporary sensibilities. By comparing the latest editions with earlier versions of the texts, The Telegraph has found hundreds of changes to Dahl’s stories.

Language related to weight, mental health, violence, gender and race has been cut and rewritten. Remember the Cloud-Men in James and the Giant Peach? They are now the Cloud-People. The Small Foxes in Fantastic Mr Fox are now female. In Matilda, a mention of Rudyard Kipling has been cut and Jane Austen added. It’s Roald Dahl, but different.

On Sunday’s CNN Newsroom, anchor Jim Acosta spoke with Suzanne Nossel of PEN America about the free expression organization’s objections, which were quote tweeted by Rushdie.

This writer would just add that getting Rushdie, CNN’s Acosta, and even Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh, on the same page in objecting to something is no small achievement, and shows the American antipathy to limiting speech still reaches most parts of politics, even if the definitions of free speech aren’t necessarily agreed upon.

ACOSTA: Augustus Gloop, one of the famous characters in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, is getting a makeover. New editions of author Roald Dahl’s classic books are being rewritten in some cases to take out language deemed offensive, such as fat, ugly, or crazy. Some of the words that are, quote unquote, being used there, now judged by modern day sensibilities. His beloved titles also include “James in The Giant Peach” and “Matilda”. Suzanne Nossal joins us now to talk about this. She’s the CEO of PEN America, a Human Rights and Free Expression Organization. Suzanne, great to see you as always. It’s been a long time, but great to catch up and talk about this, this subject. Let me ask you this. Author Salman Rushdie recently criticized some of these changes being made to these famous books. What are your thoughts on these classic works being altered?

NOSSEL: I think it’s a mistake. Look, I think the impulse here is probably a noble one. They’re trying to protect kids from stereotyping and protect prevent kids from being made to feel bad if they’re overweight or have other characteristics that might be sort of triggered by these books. But in so doing, they’re kind of gone in and excised and nipped and tucked and added things, added gratuitous lines that Roald Dahl never wrote. And it just opens up a, I think, very problematic window for people ex-post to go in and apply the standards of today to rewrite traditional literature. And look, people might agree with what the changes are to these books. Some might agree, but think about how that power might be misused. We’re right now dealing with the crisis of book banning in this country to try to excise certain topics from our public discourse. If you were to reopen literature and insist that those elements be scrubbed out, you know, you could see all kinds of wholesale changes. And so I think this is just a door that we ought not open.

ACOSTA: And I want to ask you about some of the book banning stuff in just a moment. But I know, Suzanne, you made the comment that you might be teachers might be missing a teachable moment here with some of these books to be able to say, okay, yes, there are some references made here that are insensitive to today’s ears, but it reminds me of reading Mark Twain growing up in high school and that sort of thing. I mean, obviously, you know, times change and we can reflect on literature and and talk about that.

NOSSEL: Yeah, absolutely. Look, I think teachers have to be sensitive to the sensibilities of who’s in the classroom. It’s a much more diverse classroom in many cases than it would have been 30 or 40 years ago. They need to consider how words land with different depending on their backgrounds, but that can be done by contextualizing, by talking about it, by letting people know, look, you know, you may hear a word here that you’re not accustomed to hearing that may be offensive to you. And here’s the context in which it was written. It’s not to say it was right then, but it’s something that can be discussed, that can be part of the pedagogy. I mean, we’re all going to be encountering offensive things as we go through life. And part of the role of children’s literature has always been to help us confront our fears, that which is disturbing.

Watch the clips above, via CNN and The Telegraph.

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓