Elon Musk’s Dangerous Twisting of German History

Photo by: Matthias Balk/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Over the weekend, Elon Musk spoke at a rally for the far-right German political party AfD (“Alternative für Deutschland,” or “Alternative for Germany”) and said there had been “too much of a focus on past guilt,” and it was time to “move beyond that.” Whether the world’s richest man made these comments out of ignorance or deliberate misrepresentation, they exhibit a dangerous twisting of historical fact.

Musk appeared at the AfD rally days after he was criticized for a salute gesture he made twice at President Donald Trump’s inauguration that, despite the efforts of his defenders to shrug it off, very closely resembled the physicality of a Nazi salute, was cheered by Nick Fuentes and other avowed neo-Nazis, and was generally acknowledged to be the sort of gesture it would be extremely unwise to attempt in Germany (where it is a crime) or at your workplace or another public place.

While it’s impossible to read Musk’s mind and determine whether he made the salutes to signal sympathies for neo-Nazi views, amuse himself with juvenile trolling, or just out of wild carelessness, it’s worth examining the meaning of the words he has spoken and written over the course of the last week.

“The ‘everyone is Hitler’ attack is so tired,” tweeted Musk — a comment that both downplayed the seriousness of the situation and missed the true historical lesson, an error he escalated in his speech at the AfD rally.

In his remarks made via livestream as the rally attendees loudly cheered, Musk said repeatedly he believed it was “very important” for Germans “to take pride in Germany, and being German,” and “be proud of German culture and values and not to lose that in some sort of multiculturalism that dilutes everything,” because it was good “to have unique cultures in the world.” He connected that to rejecting feelings of “past guilt”:

I think there’s, like, frankly too much of a focus on past guilt, and we need to move beyond that. People, people — children should not be guilty of the sins of their parents or even — let alone their parents, their great-grandparents maybe even. And we should be optimistic and excited about a future for Germany.

This is literally the opposite of the lesson generations of Germans have sought to embrace since the end of World War II: Vergangenheitsbewältigung, meaning “coming to terms with the past.” This octosyllabic word — no one does conceptual compound nouns as gloriously as the Germans — encompasses recognizing that regular people can end up tolerating and even participating in the growth of evil if we aren’t careful.

It’s not about demanding Germans “feel guilty” over the sins of past generations; it’s urging them to come to terms with how and why the Holocaust happened.

Adolf Hitler did not unleash this evil all by himself. It’s not even accurate to say it was caused just by Hitler and other infamous Nazi Party leaders like Joseph Goebbels, Herman Göring, Heinrich Himmler, and Rudolf Hess, or the murderous butchers at the concentration camps like Auschwitz’s “Angel of Death” Josef Mengele and Amon Göth, whose brutal operation of the Płaszów concentration camp was portrayed in the 1993 film Schindler’s List.

None of these ignominious names would have had any power without the cooperation of many regular German citizens and the inaction of many more. This encompasses the hundreds of thousands who joined the Gestapo (state secret police) or the Schutzstaffel (paramilitary “protection squadron” better known as the SS), the local police who enforced the Nuremberg Laws against Jews across the country, the millions of families who sent their children to join the Hitler Youth, and the countless bureaucrats who kept the trains leading to the ovens running on time — plus those who knowingly watched and condoned the evil flourishing in their own communities, averting their eyes and holding their tongues while millions perished.

During a college summer studying in Germany, I visited Dachau, the town in south Bavaria where the first concentration camp in Germany was opened in 1933. Now operated as a historical site and memorial to the victims, Dachau was a brutal work camp where prisoners suffered from malnutrition, disease epidemics, horrific medical experiments, torture, and mass murder. The Nazis’ official records list the intake of over 200,000 people held at Dachau and the deaths of nearly 32,000 until the camp was liberated in 1945, but the actual death count is believed to be much higher.

I wrote about this visit in an Arc Digital article for Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2019, and how I saw something even more disturbing than the row of crematoria ovens that burned countless human bodies to ash, a horror just outside the gates:

Unlike camps like Auschwitz that were located in more rural areas, Dachau’s camp is directly within its city limits. Visitors to the memorial take a short train ride from Munich, walk down picturesque Bavarian streets that look like they were designed to be featured on postcards, past homes and schools and shops…

…and then come face to face with the metal gate that says, “Arbeit Macht Frei.” The cruelly dishonest phrase — German for “work sets you free” — was also featured on the camp gates at Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, and Theresienstadt.

Its presence on the Dachau gate made it clear this was no ordinary prison.

I expected to see the crematoria and mass graves. I expected to see primitive barracks where people were crowded in conditions considered too inhumane for farm animals. I did not expect to see this horror in the middle of bakeries and bookstores, and the juxtaposition of the two scenes was jarring.

While the camp was operational, any passerby could have peered through the wide bars on that infamous gate and seen the starving, suffering, dying prisoners inside. Other than the two-story guard building around the gate, the complex is enclosed by walls or fencing only one story high in most sections.

An even more horrifying detail: Dachau’s crematoria lacked the air control technology present in modern systems, so the nauseatingly sweet odor of burning human flesh would have carried throughout the town. Contemporaneous reports from the Allied troops who liberated the camps describe the smell from the crematoria and the unsanitary conditions of so many prisoners kept in such close quarters as a stench that “covered the entire countryside…for miles around.”

Remember, the smells and sounds from Dachau’s camp did not need to travel for “miles” to reach the residents — only blocks.

As Captain Sol Nichtern, one of the American military officers who was present at the liberation of Dachau observed, the camp was “built right up against the side of the village; the houses go right up to the outer wall.”

There is simply no plausible deniability that the people of Dachau were unaware of what was happening within that camp.

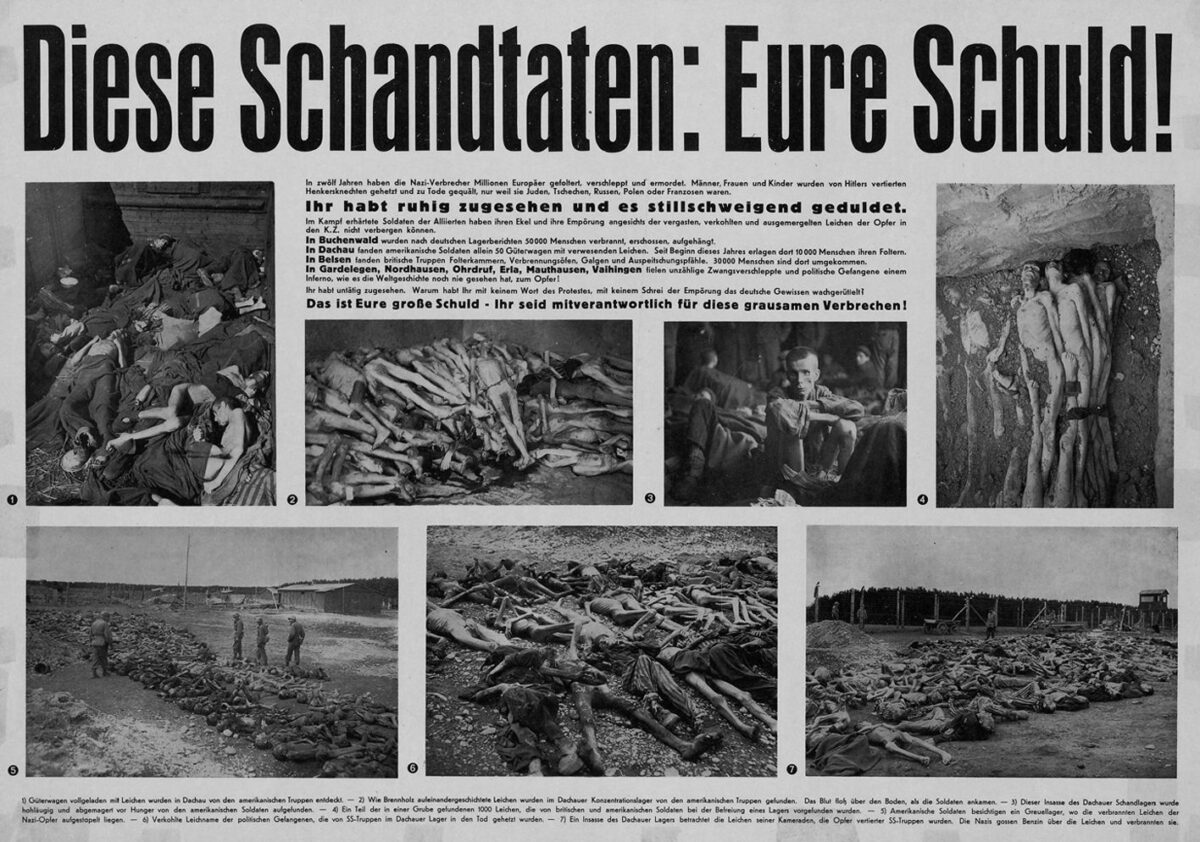

The acknowledgment of what the residents of Dachau and other cities across Germany tolerated is the foundation for the Kollektivschuld, or “collective guilt” philosophy, and it applies to those who were alive during the Holocaust who “quietly watched and tolerated it in silence,” as stated on the below poster distributed by Allied occupation forces after the war.

“Diese Schandtaten: Eure Schuld!” (“These atrocities: Your fault!”) it proclaims above images that are unflinchingly horrific.

Public domain image. Full text and English translation available here.

But this Kollektivschuld applies to neither the children too young to have known what was happening nor the generations to follow. The theory behind Vergangenheitsbewältigung is not to crush current generations with guilt, but to evoke an understanding that while it may be difficult and frightening to speak out against evil, such courage is absolutely critical for the preservation of “small-d” democratic institutions.

It’s about learning from the past, not being dragged down and oppressed by it.

It’s about wanting “Nie Wieder” (“Never Again”) to be not just a motto, but a solemn oath.

Contrary to the way Musk framed the issue, Vergangenheitsbewältigung does not mean Germans cannot be proud of Germany’s economic prowess, scientific and technological innovations, beautiful and varied geography, and the many great leaders and creative minds who came before those troubled years and the many who will come after.

But these things alone cannot operate as a bulwark against authoritarianism.

In only a few short years, the same Germany whose scientists, philosophers, musicians, artists, writers, and politicians were a driving force in the Enlightenment had crumbled into a genocidal, fascist hell. The Germany of the 1930s boasted a well-established public school system that provided both a vocational track that led to apprenticeships and one that sent students to some of the best higher-education institutions in the world — and millions of people still voted for Hitler and the Nazi Party and stood by while he consolidated power, convincing German President Paul von Hindenburg to appoint him chancellor and a compliant Reichstag to pass law after law that eroded citizens’ rights and tightened the Nazis’ grip over the country.

Throughout history, authoritarian regimes have gained populist support and official power with the same script: taking advantage of and exaggerating real economic and societal problems, promising that only the party and its leader can fix those problems, restricting free speech and the media to control information, appealing to citizens’ national or group identity with both flattery and a deliberate effort to divide them from other people they classify as foreign, outsiders, “not true patriots,” or otherwise disloyal to the nation. Those outsiders are the first to be targeted and oppressed as scapegoats, but the oppression soon spreads.

There is a vast philosophical gulf between a foolhardy, totally open borders immigration system (and the economic and security issues that can generate) and Nazism, fascism, and other authoritarian systems. The truth is, it is has never been a binary choice. Good people can advocate for reform without sacrificing decency and giving oxygen to fascists.

Like so many far-right parties before them, Germany’s AfD points to immigration, crime, and economic troubles and declares themselves to be the solution. Trump and MAGA Republicans deploy similar rhetorical tactics, campaigning on claims that a vote for a Democrat is a vote to destroy America, murder babies, and have your city overrun by drug cartels and pet-eating migrants. Only they can “Make America Great Again,” they insist.

The rhetoric from the fascists (and those who are aspirationally fascist) can be powerfully tempting because it slyly enmeshes itself in real problems and concerns. But the solutions it offers are a trick: authoritarianism has never been able to create the stable, long term economic growth that capitalist democracies do. And when a society concedes that their government can abuse the rights of any group, that abuse of power inevitably expands.

For the vast majority of Americans, you won’t be arrested, lose your job, or see your family included in Trump’s deportation roundups this week. You’re fine for now. But remember, Elon Musk and other tech billionaires have the money and power to make themselves essentially immune from any government oppression. Do you have those resources? I don’t. Most Americans don’t. Look how many former Trump employees, appointees, and allies he now calls enemies. This is a fickle, vengeful species of leader. Are you certain you and all of your family and friends will never end up on the wrong side of Trump’s wrath?

That’s why it’s vital to protect our democratic institutions, to safeguard structures that preserve the balance of power, to fight for ethics and transparency, to care about the rights of others, and to speak out clearly when influential voices amplify authoritarian views.

Today, January 27, 2025, marks Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp. Remembering the past is not about crushing people with inherited guilt, but learning the lessons to prevent resurrecting the mistakes of those previous generations.

NIE WIEDER. NEVER AGAIN.

Photo by Wolfgang Manousek on Flickr via Creative Commons License.

This article has been updated with additional information.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓