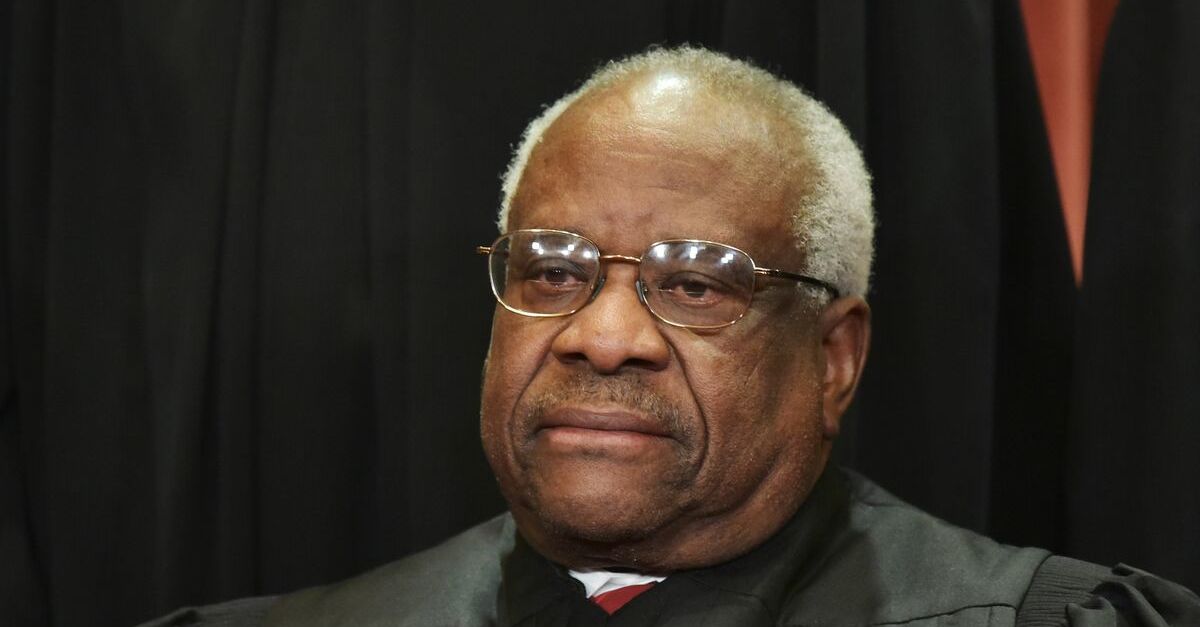

Contraception and Same-Sex Marriage Next? Justice Thomas Says Court ‘Should Reconsider’ These Cases ‘At the Earliest Opportunity’ After Overturning Roe

MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images.

The long-anticipated Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was released Friday morning, a 5-4 decision overturning the landmark cases of Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which recognized and then reaffirmed the constitutional right to an abortion. In a separate concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas suggested that cases granting rights like contraception and same-sex marriage should be reconsidered under the same legal theory.

The Mississippi law at issue in Dobbs banned virtually all abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy, with narrow exceptions for medical emergencies and “severe fetal abnormality” but not for rape or incest. In the opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, the court addressed whether various provisions of the U.S. Constitution conferred an “implicit constitutional right” to an abortion.

“The Constitution does not confer a right to abortion; Roe and Casey are overruled; and the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives,” Alito summarized the ruling at the beginning of the opinion.

Specifically, the Court held the Fourteenth Amendment’s reference to “liberty” did not confer a right to an abortion.

In interpreting what is meant by “liberty,” the Court must guard against the natural human tendency to confuse what the Fourteenth Amendment protects with the Court’s own ardent views about the liberty that Americans should enjoy. For this reason, the Court has been “reluctant” to recognize rights that are not mentioned in the Constitution.

Thomas’ concurring opinion focused on this Fourteenth Amendment issue.

“I join the opinion of the Court because it correctly holds that there is no constitutional right to abortion,” he wrote. “Respondents invoke one source for that right: the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee that no State shall ‘deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.’ The Court well explains why, under our substantive due process precedents, the purported right to abortion is not a form of “liberty” protected by the Due Process Clause. Such a right is neither ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition’ nor ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.'”

Thomas continued, saying that as the majority held in Dobbs, the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was a guarantee that the government would not deprive you of “life, liberty, or property” without complying with the law, and not in and of itself a grant of any specific rights.

“[T]he Due Process Clause at most guarantees process,” he wrote. “It does not, as the Court’s substantive due process cases suppose, ‘forbi[d] the government to infringe certain “fundamental” liberty interests at all, no matter what process is provided.'”

For that reason, he argued other “demonstrably erroneous decisions” that had been decided based on substantive due process should be reconsidered, and specifically listed Griswold v. Connecticut (1965, granting right of married persons to obtain contraceptives), Lawrence v. Texas (2003, right to engage in private, consensual sexual acts), and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015, right to same-sex marriage).

“[I]n future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell,” wrote Thomas. “Because any substantive due process decision is ‘demonstrably erroneous,’ we have a duty to ‘correct the error’ established in those precedents.”

He also called for examining whether the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment “protects any rights that are not enumerated in the Constitution and, if so, how to identify those rights.”

The majority in Dobbs, wrote Thomas, has “conclusively demonstrate[d] that abortion is not one of” the unenumerated rights protected under the Fourteenth Amendment “under any plausible interpretive approach,” but the case “does not present the opportunity to reject substantive due process entirely,” so he called for looking for “future cases” where the court could “eliminate it from our jurisprudence at the earliest opportunity.”