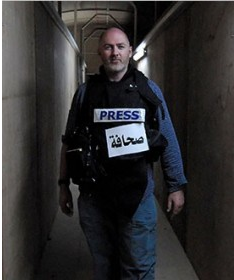

Freed NYT Reporter Reminds Us of Dangers of Real Journalism

This morning, New York Times reporter Stephen Farrell was freed from his captors in northern Afghanistan by a military raid that took the life of his interpreter. As in the case of David Rohde, the Times asked news outlets not to report on Farrell’s capture, although fortunately his was a shorter ordeal than Rohde’s.

According to Greg Mitchell of Editor & Publisher, E&P found out about Farrell’s disappearance on their own, but Times executive editor Bill Keller asked them not to publish anything. Hours later, Mitchell was freed. Who could possibly object to this tactful, sensible handling of things? This being the Internet, there’s always someone.

When New York Times reporter David Rohde was kidnapped in Afghanistan last November and held there for several months, the Times asked print and online sources, including Wikipedia, not to publish anything about the kidnapping for fear that it would further endanger Rohde’s life. (Ironically, it was Stephen Farrell who wrote the story of Rohde’s escape.) One might think that showing some restraint to help protect a human life would be a no-brainer, especially since Rohde’s kidnapping was its own story and not connected to a larger story of public interest.

But Wikipedians freaked out about the Times‘ — a print publication’s! — ability to suppress content on the Free Encyclopedia that Anyone Can Edit. One blogger wrote that “One can’t help but think that The Times – along with these other media organization – who so often sprout about a free and unhindered press; about the rights of the media to report the news without favour – have set a very bad precedent with the Rohde kidnapping.”

Well… no. What bloggers and aggregators who associate ‘reporting’ with ‘writing down my opinion’ often forget is that real reporters do real work, and often put their lives in real danger. If any given pundit suddenly vanished from the blogosphere, things probably wouldn’t change all that much, but if a Rohde or a Mitchell vanishes, a vital swathe of foreign correspondence disappears, the likes of which can’t easily be replaced. The Times — and the outlets that respected its calls not to report on the kidnappings — did the ethical, responsible thing by getting past the angels-dancing-on-pins arguments and protecting real human lives.