Michael Kinsley, Opinion, and the Evolution of Media

On Objectivity and Punditry

The ASME honor is the result of Kinsley’s lifetime of work, his role in driving opinion and conversation on diverse topics ranging from sex lives of Supreme Court Justices to the length of newspaper articles. It’s his thinking on that work itself, however, that best reflects his contributions.

The ASME honor is the result of Kinsley’s lifetime of work, his role in driving opinion and conversation on diverse topics ranging from sex lives of Supreme Court Justices to the length of newspaper articles. It’s his thinking on that work itself, however, that best reflects his contributions.

A year after John Stewart killed Crossfire, Kinsley penned an essay titled “The Twilight of Objectivity”. In the piece, Kinsley discusses this journalistic ideal:

Objectivity—the faith professed by American journalism and by its critics—is less an ideal than a conceit. It’s not that all journalists are secretly biased, or even that perfect objectivity is an admirable but unachievable goal. In fact, most reporters work hard to be objective and the best come very close. The trouble is that objectivity is a muddled concept. Many of the world’s most highly opinionated people believe with a passion that it is wrong for reporters to have any opinions at all about what they cover. These critics are people who could shed their own skins more easily than they could shed their opinions. But they expect it of journalists. It can’t be done.

In other words, Kinsley doesn’t embrace opinion for the sake of stirring subscriptions or pageviews. When Firing Line went off the air in 1999, he was interviewed for a piece in Time.

Kinsley recalls that as co-host of Crossfire, the CNN shoutfest, he once disagreed with a guest in too civil a tone. “No, no!” the producer shouted into his earpiece. “Get mad! Get mad!”… Until last week Firing Line was there to remind us that TV didn’t have to be that way.

(His Q-and-A with Slate readers after Buckley’s death sounds similar notes.)

The dissolution of Firing Line dissolved an outlet for the sharing of reasoned opinion. Kinsley kept the spirit: where the show’s aim was broadening recognition that disagreement and opinion could yield a deeper understanding of a subject, he moved to Slate – a site well-known for playing Devil’s advocate, the Internet contrarian.

In a speech at the University of Michigan last month, President Obama decried the partisan bickering in Washington, how elected officials of both sides of the aisle were, following the lead of Kinsley’s CNN producer, getting mad.

Well, if you turn on the news today – particularly one of the cable channels – you can see why even a kindergartener would ask [if people are being nice]. We’ve got politicians calling each other all sorts of unflattering names. Pundits and talking heads shout at each other. The media tends to play up every hint of conflict, because it makes for a sexier story – which means anyone interested in getting coverage feels compelled to make the most outrageous comments.

Kinsley addressed this exact issue four years prior in “The Twilight Of Objectivity,” recognizing that the arguments held for media of any format:

Kinsley addressed this exact issue four years prior in “The Twilight Of Objectivity,” recognizing that the arguments held for media of any format:

Much of today’s opinion journalism, especially on TV, is not a great advertisement for the notion that American journalism could be improved by more opinion and less effort at objectivity. But that’s because the conditions under which much opinion journalism is practiced today make honesty harder and doubt practically impossible…. TV pundits need to radiate certainty for the sake of their careers. As Lou Dobbs has demonstrated, this doesn’t mean you can’t change your mind, as long as you are as certain in your opinion today as you were of the opposite opinion a couple of days ago.

But if opinion journalism became the norm, rather than a somewhat discredited exception to the norm, it might not be so often reduced to a parody of itself. Unless, of course, I am completely wrong.

That last caveat is more than a joke. It’s the deepest fear of any pundit that his or her presentation is uncovered as an intentional or unwitting fraud; it’s the worry of every innovator that there is no question that his invention answers. The surest way to elide these fears is to present an argument robustly and in good faith, to vigorously expose new tools to challenges. Kinsley can suggest he might be wrong because if he understands that even if he is, the conversation is nonetheless advanced.

Decades into his career and years into the complete upheaval of the media itself, Kinsley is still advancing it. One of the few old-media thinkers to adapt in – and advance – the new media space, Kinsley somehow continues to straddle the two. Nominated for tomorrow’s Mirror Awards for essays in The Washington Post and The New York Times, he’s signed on with the Atlantic – an old-school media property known for aggressively pushing into the future. Meanwhile his brainchild, Slate, has outlasted its more established old-media sibling at the Washington Post company…Newsweek. And today, as Crossfire is cited as re-cited as the way to save CNN and pundits clamor for President Obama to fix the oil spill by shaking his fist and showing just how mad he is, his arguments against invented and inchoate anger from a decade ago could not be more relevant today.

The flipside, of course, is that you have to be mad about something. The kicker to his piece on the Tea Party in this month’s Atlantic:

Our new national motto is from the movie Network: “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore.” And what is “this?” Ask not.

The piece (“My Country, ‘Tis of Me”) takes issue with the movement as much for its lack of core principles and self-exploration as it does its politics. He’s more than happy to engage on the issues (“Principled libertarianism is an interesting and even tempting idea,” he muses in a typically wonkish way) – but when he looks for something to actually engage with in the Tea Party, he comes up empty. It’s not that he disagrees with them on principle – he just disagrees with their utter lack thereof. And that, in a nutshell, is what Kinsley is all about – ideas based on innovation, opinions based on facts, moving forward instead of backward. This hollowness, Kinsley seems to argue, is what is un-American about the Tea Party as anything. In a nation constructed of millions of opinions, the most undemocratic thing one can do is have one you couldn’t back up on Firing Line.

Unless, of course, I am completely wrong.

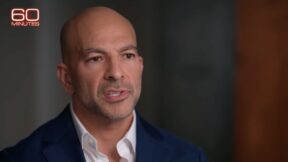

Photos of Kinsley taken from SFGate, New York Times, Harvard Law website. Great interview by then-Harvard Law dean Elena Kagan here; CNN Crossfire featuring Frank Zappa found here.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.

New: The Mediaite One-Sheet "Newsletter of Newsletters"

Your daily summary and analysis of what the many, many media newsletters are saying and reporting. Subscribe now!

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓