Louvre Heist Exposes Years of Security Failures, Including Passwords a Child Could Have Guessed

The brazen October heist at The Louvre may have looked like a shock from the outside, but French government files show the exact risk had been neglected when spelled out in audit after audit for years, flagging dangerously outdated systems and even a surveillance system password that was “LOUVRE.”

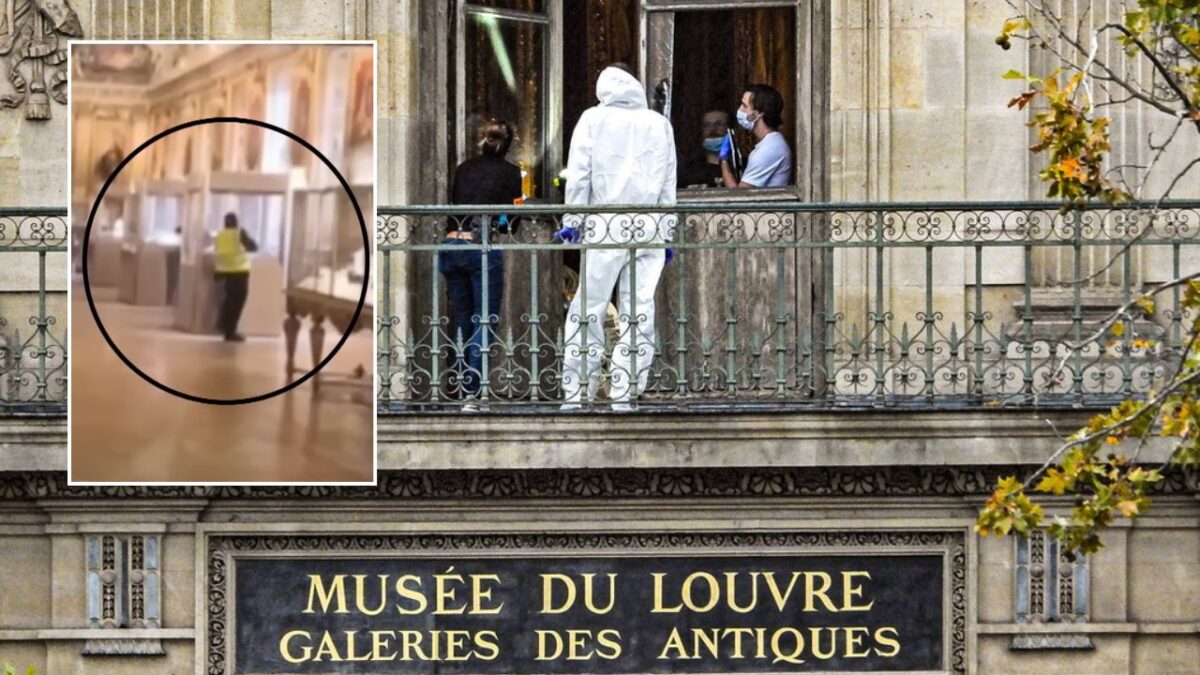

The museum is still reeling from the cost, both financial and reputational, of the astonishing daylight robbery that saw thieves escape with a haul of Napoleonic jewels in just seven minutes.

Armed with power tools and dressed in high-visibility jackets, the gang broke through a second-floor window of the country’s most famous museum, accessing the Apollon gallery via a maintenance area, where the French crown jewels are kept, before smashing display cases, and vanishing on motorbikes before guards could respond.

Now the aftermath has become its own slow-motion scandal: how does the most famous museum on Earth end up with a security infrastructure that a French state audit once proved was vulnerable to passwords like “LOUVRE”?

French newspaper Liberation has looked back more than a decade, revealing a grim bureaucratic archaeology and a full paper trail of warnings demanding changes to old systems and passwords anyone could crack.

In 2014, the investigation reported, experts from France’s National Agency for the Security of Information Systems wrote in a confidential 26-page report that “the applications and systems deployed on the security network present numerous vulnerabilities.” They warned hackers could remotely alter badge access or manipulate video feeds. The Louvre never confirmed how many of the fixes were adopted.

Another report, in 2017, by the National Institute for Advanced Studies in Security and Justice, concluded that “serious deficiencies were observed in the overall system” and that the museum could “no longer ignore the potential risk of a breach.”

Yet by 2019, paperwork suggests several core systems were already “beyond repair.” One Thales-designed program dating to 2003 was still running on Windows Server 2003 – unsupported since 2015 – and in 2025 was formally classed as “software that cannot be updated.” And, you guessed it, the password was “THALES.”

The embarrassment, it appears, now lies in the audit trail. The museum was warned, often and for years.

New: The Mediaite One-Sheet "Newsletter of Newsletters"

Your daily summary and analysis of what the many, many media newsletters are saying and reporting. Subscribe now!

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓