Is The American Press Another Institution That Needs Government Help?

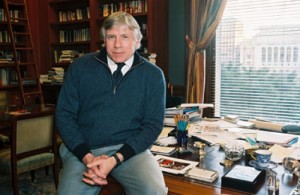

We’ve been hearing about the American press’ survival crisis for quite a while now. Amid assertions that “journalism is dying,” various publications have refocused their mission or resorted to paywalls. Today in the Wall Street Journal, Columbia University’s President Lee Bollinger makes the case for a different kind of solution: government involvement.

We’ve been hearing about the American press’ survival crisis for quite a while now. Amid assertions that “journalism is dying,” various publications have refocused their mission or resorted to paywalls. Today in the Wall Street Journal, Columbia University’s President Lee Bollinger makes the case for a different kind of solution: government involvement.

Bollinger notes that we’ve “entered a momentous period in the history of the American press” where the Internet is affecting the industry just as significantly as the printing press did in the 15th century. This is a comparison we’ve heard before, but Bollinger’s argument for government involvement is one that is rarely given legitimate consideration:

The idea of public funding for the press stirs deep unease in American culture. To many it seems inconsistent with our strong commitment, embodied in the First Amendment, to having a free press capable of speaking truth to power and to all of us. This press is a kind of public trust, a fourth branch of government. Can it be trusted when the state helps pay for it?

American journalism is not just the product of the free market, but of a hybrid system of private enterprise and public support.

The piece then brings up an interesting example: the British Broadcasting Corporation. The BBC’s model is a unique one:

Such news comes to us courtesy of British citizens who pay a TV license fee to support the BBC and taxes to support the World Service. The reliable public funding structure, as well as a set of professional norms that protect editorial freedom, has yielded a highly respected and globally powerful journalistic institution.

Bollinger appropriately brings up the BBC model, which does — as he says — support his argument. However, it is also worth noting that the though the BBC is a widely respected news organization, the license fee has been a source of debate in Britain for many years now. The concept is not entirely popular among the country’s citizens, with some of its critics comparing it to a poll tax and others calling for its removal.

But Bollinger lists more examples, and he makes a valid argument in doing so. He also makes an interesting point about the industry’s reliance on advertising:

To take a very current example, we trust our great newspapers to collect millions of dollars in advertising from BP while reporting without fear or favor on the company’s environmental record only because of a professional culture that insulates revenue from news judgment.

He also says we need an “American broadcasting system with full journalistic independence that can provide the news we need.” Yes, we do. It’s often said that a free press is the cornerstone of democracy — and in a country that touts its democratic values, our press should not, despite unstable business models, lose sight of what its mission is.