Free Speech Group Lambasts Stanford for ‘Coercive’ Process After Student Reported for Reading ‘Mein Kampf’

Kirby Lee via AP

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) sent a letter to administrators at Stanford University after the campus paper reported that a “Protected Identity Harm report” had been filed regarding a student spotted reading “Mein Kampf,” Adolf Hitler’s autobiography that would serve as a manifesto for the Nazi regime and his rise to power.

According to The Stanford Daily, a Snapchat screenshot showing a student reading the book was submitted to university officials under the PIH process, which it described as “the University’s system to address incidents where a student or community member feels attacked due to their identity.”

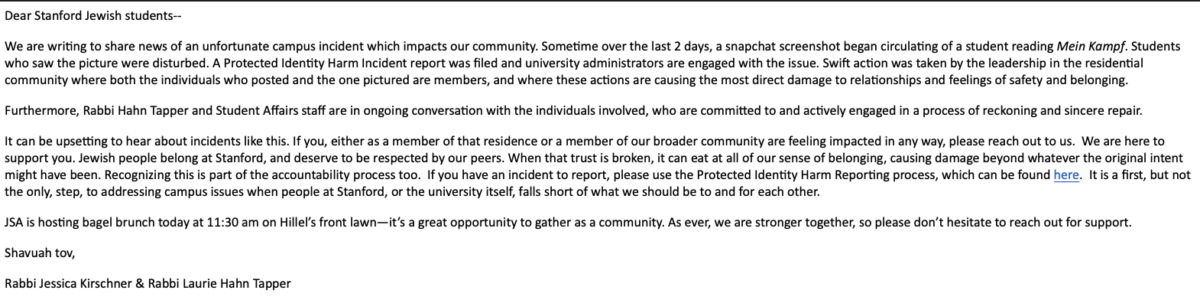

“Swift action was taken by the leadership in the residential community where both the individuals who posted and the one pictured are members, and where these actions are causing the most direct damage to relationships and feelings of safety and belonging,” wrote Hillel Stanford’s Rabbi Jessica Kirschner and Rabbi Laurie Hahn Tapper in an email message sent to Jewish students at Stanford. “It can be upsetting to hear about incidents like this…Jewish people belong at Stanford, and deserve to be respected by our peers.”

Screenshot via Stanford Review (edited to remove personal contact information).

Kirschner and Hahn Tapper also wrote that this incident had “broken” the sense of trust on campus, which can cause “damage beyond whatever the original intent might have been,” and called for “accountability.”

The university’s Offices of Student Affairs and Office of Religious and Spiritual Life were “actively working with students involved to address the issue and mend relationships in the community,” the Daily reported.

Missing from any of the reporting is any mention whatsoever that the student was doing anything other than reading the book, which Hitler began writing while imprisoned after a failed coup attempt and published in 1925. There are no accusations the student was voicing support for the antisemitic, nationalist, and authoritarian views Hitler outlines in his writing.

The involvement of the university and implementation of the PIH process “looks to be a case study in how bias reporting systems chill speech,” wrote FIRE’s Graham Piro and Alex Morey.

“Reading a book on a college campus should not prompt formal administrative intervention,” they continued, expressing concern that the PIH system was “coercive” and “can be used, as here, to target and reform views students or administrators dislike, while cloaking it as a purely educational exercise”:

Administrators with disciplinary authority formally notifying students they’ve been accused of “harm,” when they’ve done nothing more than read a book, and asking them to “acknowledge” what they’ve done and “change” their ways through restorative justice-type exercises undoubtedly chills student speech…

The power differential between university administrators and students is significant. When the Office of Student Affairs, which has disciplinary authority, formally contacts a student about a complaint filed about their conduct and asks them to engage in a reconciliation process to address alleged harm, that student is unlikely to interpret the request as genuinely voluntary. Rather, such an invitation strongly suggests a student’s actions were problematic, and they may accordingly self-censor…

Universities cannot institute Orwellian reporting systems that pressure students to confess, “take accountability,” and promise to “change” — all for reading the wrong book.

Students who object to a peer’s reading material are not without recourse. They can ignore it, or employ their own expressive rights to offer personal critiques or even harsh criticism. Stanford would also be wise, when difficult issues arise on campus, to convene discussion groups, town halls, or other expressive events to promote common understanding and tolerance. But universities cannot wield their institutional authority to force compliance with any particular views or particular students’ sensitivities.

As FIRE and others have noted, Mein Kampf (German for “My Struggle”), was required reading in at least one recent Humanities course taught at Stanford and is currently available to be checked out of the university’s library.

I double majored in Political Science and German at the University of Florida, and read excerpts of the book myself (in both English and the original language). I personally thought the views expressed within were offensive and detestable, but it is a document of historic significance, and I understood why it was part of the curriculum in several of my classes.

Other Twitter users recalled their own college experiences, and noted the distinction between studying antisemitism and actually committing antisemitic acts — as well as a number who pointed out how dreadfully mendacious and tedious Hitler’s prose was.

https://twitter.com/bendreyfuss/status/1618689072406593536?s=20&t=W-zMiThpsnpNTwExWIlFpg

https://twitter.com/bendreyfuss/status/1618689618941206528?s=20&t=W-zMiThpsnpNTwExWIlFpg

https://twitter.com/TolkienesqueDem/status/1618694704924868608?s=20&t=s4-SztlBwWzSsW1TWJwpjg

An article by Julia Steinberg at The Stanford Review added some additional reporting, noting there was some chatter on local campus networks that the photo had been an ill-conceived joke, perhaps done under the influence of alcohol.

But regardless of whether Mein Kampf was being “read for class or used for a drunken photo shoot,” wrote Steinberg, the incident was “not worth widespread condemnation” and “the public outrage” was “undeserved.” She went on to advocate for upholding the university’s “liberal values” by encouraging students to engage with offensive and controversial books:

No matter what the context of the photo was, the community’s reaction stands in opposition to the liberal values of the university. The email to the Jewish Students Association email list, the filing of a Protected Identity Harm Incident, and condemnation added by the Stanford Daily article about a “photo of the student reading [Mein Kampf]” reveals how fast the Stanford community will jump on the censorship train in the name of fighting oppression. No matter the context, we should not chastise students for reading controversial books, and we certainly should not spread an institutional message that “feelings of safety and belonging” should be prioritized above academic freedom to read controversial books or the personal freedom to make an off-kilter joke.

Students should be exposed to banned books and uncomfortable ideas as only engaging with ideas outside of one’s comfort zone can one be pushed to strengthen one’s intellect. The ethos of ignoring, rather than engaging with, ‘offensive texts’ forces students into a state of hyper-fragility that “disturbed” them (in the words of Rabbi Kirschner and Rabbi Hahn Tapper). Any education that prioritizes student comfort over the pursuit of knowledge and full understanding is one that underestimates students’ ability to grapple with complex and perhaps sensitive topics. Not only does the ethos of ignoring sensitive texts patronize students, those who are not exposed to dangerous ideas—such as those articulated in Mein Kampf—will fail to respond to them in the real world.

“[I]f we ignore ideologies that we find problematic, we might lose sight of the grievances that make these ideologies attractive to many. Perhaps more importantly, we can only learn to debate and eliminate dangerous ideologies by wholly understanding their arguments,” Steinberg concluded, pointing out that one of the lessons of Mein Kampf was “how the suppression of speech is closely tied to fascist government,” and voicing support for “academic freedom,” including “the freedom to read whatever one likes.”

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓