Yes, It’s a Cover-Up: The Epstein Files and a DOJ Asking You to Trust It

The Epstein files have evolved from a conspiracy curiosity to one of the biggest ongoing stories in Washington. As the gap between what Congress ordered released and what the public has actually seen continues to widen, one term remains conspicuously absent from mainstream coverage: cover-up.

On Saturday, Attorney General Pam Bondi informed Congress that “all” Epstein-related records required under the Act have now been released and that nothing was withheld for embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity. That claim cannot be independently verified by anyone outside the DOJ. There is no independent audit, no outside review, and no mechanism for confirming it beyond taking the government at its word.

To wit: Congress called for transparency by passing a bipartisan bill demanding the Epstein files get released. Under intense political pressure, President Donald Trump reversed his position and signed it into law. The public has been handed what we are told is roughly half of all pages the DOJ has, and mostly with names of powerful men redacted.

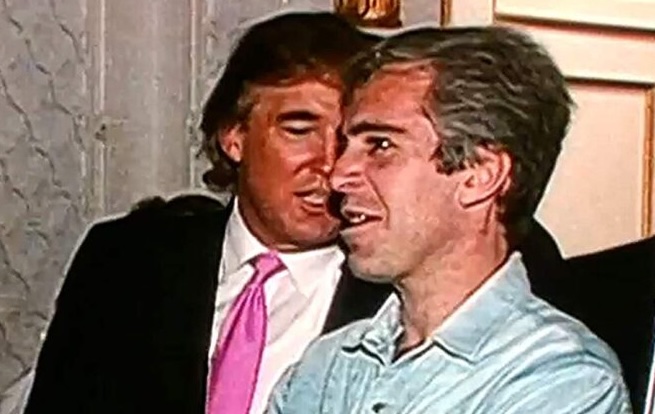

This is a horrific story about girls who were trafficked and abused. It is also about a wealthy predator who surrounded himself with famous men, political donors, business titans, and public officials. Lawmakers in both parties said the public deserved to see the full record and passed a law to force disclosure. What followed has been slow disclosures, heavy redactions, and official insistence that the country move on.

That is a cover-up.

The administration has also managed to create the worst possible information environment through its own actions. Remember the failed photo op of MAGA influencers parading a binder filled with public information? Bondi publicly claiming she had a list on her desk a year ago? The DOJ letter declaring the case closed while pages remain unseen? Trump calling the whole thing a Democratic hoax? All of these raise public uncertainty that the Trump administration is not being straight with the nation.

Even Marjorie Taylor Greene, hardly a Democratic critic, has said publicly that Trump ‘fought the hardest’ to stop the files from being released and called it the ‘biggest political miscalculation’ of his career.”

Each move has been presented as “transparency” while functioning as delay, and the cumulative effect is an atmosphere where conspiracy theories don’t just survive — they start to make sense. When the government doles out information in calculated increments while insisting the public should be satisfied, distrust isn’t a failure of the audience. It’s a predictable consequence

Journalists and newsrooms have resisted reaching the “cover-up” conclusion for understandable reasons. Calling something a cover-up implies intent, and intent is difficult to prove without internal documents that make motive explicit. Editors know the legal risks, and they know how quickly a loaded word can damage credibility if it outruns the evidence. The professional instinct is to wait for the email, the whistleblower, or the document that removes all doubt.

In the Epstein case, however, that instinct gives the DOJ a significant structural advantage, because the department controls the very documents that would establish whether anything improper occurred in the first place.

Said more plainly, the only people who can prove there is, in fact, no cover-up are the very same people accused of running one.

Consider how this typically plays out. A reporter files for the remaining records under the transparency law. The DOJ redacts pages containing names and cites privacy rules or an ongoing review. The reporter asks for the legal basis for those redactions and whether there is a timeline for full compliance. The department replies that it is complying with the statute and denies deliberate suppression. The resulting story includes that denial, accurately reflects the official position, and moves on. The files remain sealed, and when another reporter tries again, the answer looks much the same.

The coverage is technically correct, but it leaves readers no closer to understanding why legally mandated transparency continues to stall.

The burden of proof falls on journalists, while the underlying evidence sits inside the DOJ. If the standard for using the word “cover-up” requires documentary proof of motive that only the executive branch can access, the threshold becomes nearly impossible to meet. The Trump administration can claim good faith, point to procedure, and declare the matter closed, all while retaining control over what the public sees.

The broad outlines are not in dispute. Congress required disclosure. Full disclosure has not happened. The withheld material involves powerful people. Political leaders are signaling fatigue even though the public record remains incomplete. In almost any other context, the alignment of secrecy and convenience would prompt sharper language, not softer phrasing.

This instinct to narrow access when reputations are at stake runs across parties. The Bush administration delayed torture memos under the banner of declassification review. The Obama administration fought disclosure of drone strike legal opinions. The Clinton White House challenged subpoenas on executive privilege grounds. Different eras, same reflex.

The Epstein files stand apart in one crucial respect. There is no credible national security interest at stake. These records relate to a sex trafficking operation and the influential figures who orbited it. Congress ordered transparency, but another branch of government still decides how much the public gets to see. If national security is not the justification for withholding names and records, what is?

The press has used the word “cover-up” before. *The Washington Post* editorial page called Watergate a cover-up before every tape was turned over. Reporters described Iran-Contra that way while they were still mapping the chain of command. Seymour Hersh did not wait for every internal memo before exposing what happened at Abu Ghraib. In each case, journalists recognized a pattern of concealment and named it while evidence continued to surface.

The word did not wait for perfect proof. It helped force more of it into view.

A cover-up can move through procedure as easily as through conspiracy. It can look like strategic redactions and narrowed scope, paired with official insistence that the public has seen enough. It can depend on a press corps that sets an evidentiary bar only the government has the power to clear.

Now Bondi says the DOJ has fully complied. If that is true, the department should welcome independent verification. If it is not, only the department would know.

The public is being asked to accept that because the government says so. There is no independent audit. No outside verification. No mechanism beyond trust — in a case about a sex trafficker whose entire operation depended on powerful people trusting each other to stay quiet.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.

New: The Mediaite One-Sheet "Newsletter of Newsletters"

Your daily summary and analysis of what the many, many media newsletters are saying and reporting. Subscribe now!

Comments

↓ Scroll down for comments ↓